Galvanized Parabola, 1991, Galvanized steel, 262 x 170 cm

»Bernhard Kirschenbaum«

Stockholm, May 19, 2017 - June 22, 2017

That an artist, sooner or later in life, chooses to make a self-portrait can be seen as inevitable. The self-portrait is part of a journey toward self knowledge that lies more or less embedded in artistic practice as a whole. When Bernard Kirschenbaum (1924 – 2016) made his self-portrait in 1980 he chose to make it in the form of 13 polygons interlaced with one another. They were made with great craftsmanship, naturally, in cherry tree wood.

It is not exclusively the choice of materials that render a self-portrait a close likeness. Kirschenbaum had great insight into ”divine geometry” and its almost inexhaustible possibilities. On a practical level he had encountered and used it working as an architect with a speciality in geodesic domes. He learned from Buckminster Fuller and developed upon his mentor's ideas. It was when he received a commission for a geodesic dome as a home for Susan Weil that he, in his own words, built himself into the house and married the client. The geometric framework offered, literally, space also for love.

From there Kirschenbaum shifted focus from architectural functionality to the poetic potential of geometry and construction. He would come to share Susan Weil's interest for Persian poetry, in particular Rumi, and produced, like Weil, artist books on the subtle word craft of the poet. At the same time he developed his own software systems in the digital realm which revealed the proximity and dialog between divine geometry and, equally divine, chance. Both of which he could connect to his studies of nature as a youth.

As late as 2012 he programmed computer code to make eight drawings. Using polygons as the basic elements, their interaction is generated by chance. Of this suite of drawings, titled ”Accumulations”, his daughter Sara Kirschenbaum writes: ”These drawings distill his love for geometry and authentic serendipity.”

The search for natural points of contact between art and science continues to be an area of investigation in our time, though frequently reducing itself to fading embers. For Bernard Kirschenbaum these connections are visible in every work. Rationality, it turns out, serves irrationality and vice versa. The author of these lines is not aware to what extent Kirschenbaum was interested in his Jewish heritage. But, as in the work of his older peer Barnett Newman, Kirschenbaum’s works recall the Ha-Makom of the Kabbala, understood as The Place. The works take their place in the room with a gentle self-evidence that encompasses the viewer.

Olle Granath

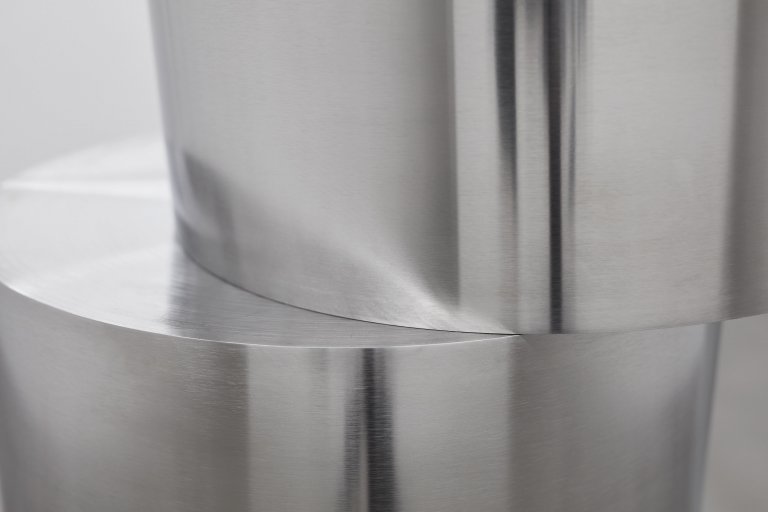

Galvanized Parabola, 1991, Galvanized steel, 262 x 170 cm

Galvanized Parabola, 1991, Galvanized steel, 262 x 170 cm

Installation view

Monument to the Earth, 1981, Polyurethane on wood, 225 x 550 cm

Monument to the Earth, 1981, Polyurethane on wood, 225 x 550 cm

Monument to the Earth, detail

Way 2, 1976, Stainless steel, 305 cm ø 30 cm

Way 2, 1976, Stainless steel, 305 cm ø 30 cm

Way 2, detail

Installation view

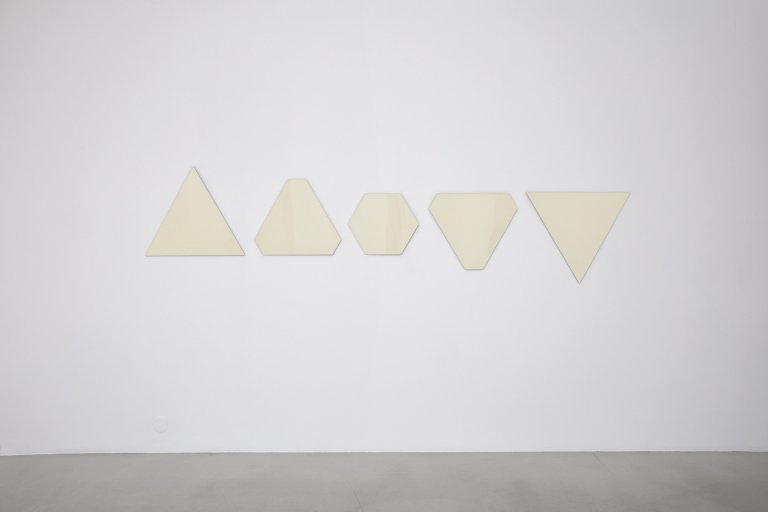

Transformation, 1971, Acrylic glass, paper and metal, 5 parts 59 x 68.5 cm each

Transformation, 1971, Acrylic glass, paper and metal, 5 parts 59 x 68.5 cm each

Installation view

Night, 1981, Lacquered steel, 52 x 105 cm, Edition of 15